In loving memory of Chai Chingburanakit, loving father, grandfather, and friend. He was a very stylish man indeed.

May his memory be a blessing to all.

After sending Life Is Full of Hard Choices last time, someone I deeply respect emailed me that I should write about inflation risk as a follow-up piece.

And so we shall.

But first, I want to mention my recent conversation with Mike Green on TREUSSARD TALKS.

Mike is a very serious student of economics who made very serious waves near the end of 2025 when he wrote a piece about poverty in America.

He went viral, as the expression goes, by suggesting the poverty line may be closer to $140,000 than the official $40,000.

This is a must-listen conversation.

The first 45 minutes are about markets, including what happens when passive investing reaches a tipping point that can disregulate markets.

Starting at minute 45:00, we dig in on the topic of poverty and financial precarity in modern-day America.

Direct links to my conversation with Mike Green below:

Now, let's talk about inflation risk…

In the previous piece, I made the point that, from late 2022 to around the middle of 2025, life was simple (at least in one very specific way).

You could invest in relatively low-risk securities—e.g., U.S. Treasury bills—and earn about 5% before taxes and inflation.

You then paid your federal taxes (Treasuries are not taxed at the state and local level), and you could put up with a reasonable amount of inflation (like 2.5%)… and still accrue wealth on an after-tax and after-inflation basis.

However fleeting, it was a pretty neat time to be an investor.

That window has largely closed now.

We are back to a world in which, by the time you're done paying your taxes and covering the bite of even moderate inflation, you're lucky to be treading water.

This is making people say all sorts of things that I don't totally understand, like "TINA: There Is No Alternative (to stocks)."

Of course, there are alternatives.

None of them perfect.

But hey, stocks aren't perfect either…

In case you didn't know—even in the country with arguably one of the best long-term historical experiences with equity investing in modern history—once in a while, the stock market drops by 20%, 30%, or even 50% before it finds a bottom.

I know that we are evolutionarily designed to have short memories, but from October 9, 2007, to March 9, 2009, the S&P 500 dropped a proper 55%, give or take a few decimal points.

Anyway, back to "having alternatives."

My friendly reader with a distinguished investment career suggested that I should write about TIPS.

That stands for Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities.

As luck would have it, TIPS are part of the family lore, as my father-in-law is Boston University Professor Zvi Bodie, and he's been known for a long time as "Mr. TIPS."

Zvi Bodie on Wisdom, Risk, and the Functions of Finance

Podcast Episode • June 25, 2025

In this deeply personal conversation, I sit down with my father-in-law and former doctoral advisor, Zvi Bodie—one of the most influential financial economists of the past half-century. Zvi traces his journey from Brooklyn plumber's son to studying under Paul Samuelson at MIT, where he helped pioneer modern financial economics.

We explore his groundbreaking work proving stocks aren't effective inflation hedges, why the "stocks for the long run" argument contradicts option pricing theory, the LTCM crisis from an insider's perspective, and why he recently co-authored a new textbook emphasizing option pricing over traditional valuation models.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, and PodBean

I had kept TIPS out of the conversation last time because they are sufficiently different from traditional U.S. Treasury bonds that they can be perceived to be "complicated."

As it turns out, what makes them complicated is also what makes them special (which incidentally is also true of many of us…).

TIPS are issued by the U.S. Treasury, which to date has an admirable record of keeping its promises. That's special and simple.

The thing that's different is that, as you might have guessed from the name, they are inflation-protected.

When you hold them, you earn interest AND you get inflation compensation via regular adjustments to the amount you receive when they mature (the bond's notional value), which is meant to offset the corrosive effects of consumer price inflation on the value of a dollar.

To prevent "reverse sticker shock," note that the interest rate on TIPS appears much lower than traditional Treasuries.

But remember: With traditional Treasuries, you get a higher coupon rate but you're on your own to cover inflation out of that income.

With TIPS, you get a lower coupon but the U.S. Treasury has you covered for inflation on the backend (before you give some back in the form of taxes).

In other words:

Traditional Treasuries have known dollar returns and unknown after-inflation returns.

TIPS have unknown dollar returns but known after-inflation returns.

If you ever needed an example where uncertainty does not equal risk, there you have it.

The 20-year TIPS yield was 2.35% on Friday, January 23, 2026. That's near the top of the historical range, with the exception of Financial Crisis–era yields.

Whether that's enough to be attractive—particularly if you hold them in a taxable account—is up to you.

But from a pure valuation standpoint, the interest you can earn at the moment on top of inflation for the next 20 years, backed by the U.S. government, is roughly in the top 10% of historical yields going back to 2004 (as far back as we have data, from the Federal Reserve).

And if you think stocks have got you covered if we get inflation in the U.S. again like we did back in the 1970s, boy, do I have some historical data to show you...

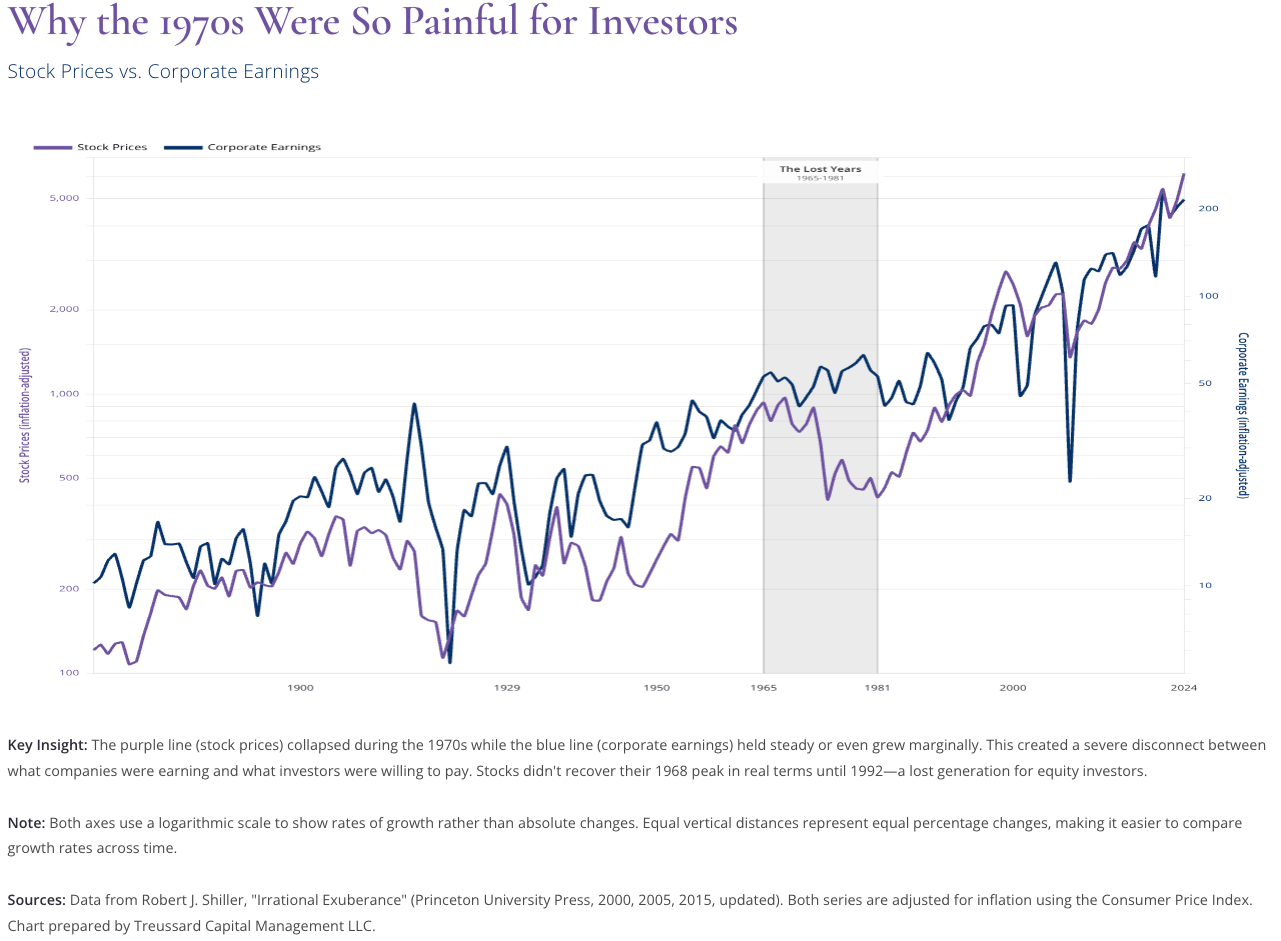

Look carefully at the shaded area, that’s 1965 to 1981.

Blue is corporate earnings and purple is stock prices, both adjusted for inflation.

Notice which one is down roughly 50% over the 1970s… It’s not earnings.

To go with this graph, I give you the opening paragraph from Nobel-winning economist Franco Modigliani and his co-author Richard A. Cohn’s article in the Financial Analysts Journal in 1979 (The piece's title is "Inflation, Rational Valuation and the Market" if you want to look it up).

"UNTIL their poor performance in recent years, equities had traditionally been regarded as an ideal hedge against inflation. Equities are claims against physical assets, whose real returns should remain unaffected by inflation. Furthermore, many equities represent claims against levered assets, and inflation is supposed to benefit debtors. Today, the level of the Standard & Poor's 500 stock index, when measured in nominal terms, is approximately the same as it was in the second half of the 1960s. In real terms, the S&P has fallen to around 60 per cent of its 1965-66 level, or 55 per cent of its 1968 peak."

Turned out that this 60% decline in net-of-inflation stock prices could be ascribed to "systematic investor errors," in economist speak. Simply put, it didn't make sense. But not making sense did not make it any less everyone's reality. So much for stocks being a reliable inflation hedge (Remember what they say “assuming” makes of you or me).

Now back to my conversation with Mike Green.

This was a twofer.

Two distinct topics, both discussed in depth.

The more I think about it, the more I actually suspect they're not wholly unconnected, but let's take them one at a time.

First, the rise of passive investing and what a "singularity moment" might look like.

In the old days, most normal, working people had pensions.

Rich people had excess money they would contribute to the engine of capitalism via the stock market. They would pick specific companies they believed in, in hopes of compounding excess wealth over the long haul.

Then, pensions started disappearing, as the interest-rate environment changed and as the relationship between employers and employees became more fleeting.

We "innovated" the ubiquitous 401(k) plan as a substitute. Workers would contribute tax-incentivized dollars now to invest towards their retirement.

In a do-no-harm kind of way, the "royal we" realized it didn't make a whole lot of sense for dentists, rabbis, and car mechanics to play stock pickers as a side hustle, and thus the passive investing index-fund revolution was underway.

On the face of it, all a good thing, at least in the sense of the "ownership society" with reasonable guardrails.

To start, however, Mike rightly points out that markets were never designed to be retirement vehicles. They were meant to help us price securities efficiently and to guide capital to where it needed to go to move us forward as a society.

In short, we started asking markets to do more than they were meant to do. But that's no reason to feel bad for them, per se. Markets are not people. They're not even horses. They don't require our compassion.

But an issue quickly became apparent.

Markets were supposed to work by inflicting episodic pain on investors when they got carried away. Prices went up too fast? A proper whack would put speculators in their place. Problem solved.

Except now people's retirements were riding on the stock market. We could not "afford" for the market to drop by much before grandma couldn't pay her bills. And so the "Greenspan put" was born.

But there was another issue developing slowly under the surface.

The passive indexing revolution meant money would hit the U.S. stock market every two weeks with every 401(k) contribution. We call that price-insensitive behavior.

Stocks are cheap? Here is $100.

Stocks are expensive? Here is $100.

As long as I have a job, here is my $100.

Like clockwork. No knowledge required. Not even an opinion. When this type of blind, mechanical investing hits a tipping point, Mike tells us that markets can break down.

He has good economic theory on his side, including a seminal paper by Grossman and Stiglitz (1980): in the absence of information, all normal trading stops. The only remaining trading is noise trading—you take money out to pay for groceries in retirement, that sort of thing. In that world, the only prices that clear trades are zero or infinity.

That's a market that breaks down.

And as much as people want to dismiss Mike as a Cassandra, I do worry about what happens if we get a major wave of unemployment. The contributions stop. The orders all come to sell to cover living expenses.

Then what?

And then there is the issue of precarity in America.

In case you haven't noticed, we're having a very serious public policy debate around what it means to live in a K-shaped, bifurcated economy, where one set of people is doing very well and the other is truly struggling.

This debate is crucial as we sort out what 21st Century America is going to look like.

Cohesive or not.

Prospering or not.

Functional or not.

This is deeply political stuff, in the sense that when you get to the bottom of most 'isms—communism, capitalism, fascism—there is a core economic question: who gets what?

Mike stumbled into this political bar fight when he tried to answer a simple question: "Can a middle-class family afford the kind of life it could have enjoyed in the 1960s?"

His answer, after much data work: No sir, not even a little.

In fact, he kept digging and learned things about how the poverty line is calculated that made him “feel sick to his stomach,” as he put it during our conversation on TREUSSARD TALKS.

We accidentally adopted a formula for the poverty line in the 1960s that bears no resemblance to what it means to cover the expenses of a family in America in 2026.

They say $40,000. He says $140,000.

You can see how this kind of gap between official definitions and Mike's math homework could upset people.

It could also explain why people are hurting, trying to climb a very tall economic mountain indeed.

And unlike markets, people deserve all the empathy and compassion we can cobble together if we're going to pull through this very dark moment in America as one united and prosperous people.

I hope you'll listen to that part of my conversation with Mike Green. That starts right around minute 45:00.

Disclaimer: All content here, including but not limited to charts and other media, is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. Treussard Capital Management LLC is a registered investment adviser. All investments involve risk and loss of principal is possible. Historical data and past performance are no guarantee of future outcomes.

Full disclaimers: https://www.treussard.com/disclosures-and-disclaimers.